Digital Humanities (DH) projects are often interdisciplinary and require the help individuals from a variety of backgrounds. Perhaps the most important people for these projects are librarians. At my university, I am lucky in that there is an entire DH initiative based out of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences as well as the library. Many of the staff members who train us in DH methods and advise our projects work directly for the library. They have also served as excellent liaisons between students and the wide variety of library services that are often hidden.

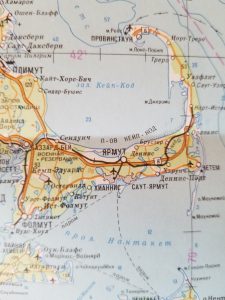

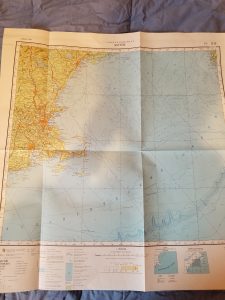

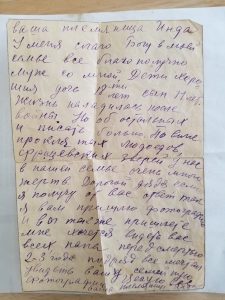

My dissertation incorporates a large DH digital mapping component. I’m tracking the locations of German prisoner of war camps in the USSR from 1941-1956 as a way to make a large-scale economic argument about the long-lasting detainment of the German POWs after the end of the war in 1945. One stage of the mapping process that I’m about to undertake is layering the locations of the camps over Soviet produced economic geography maps from the 1940s to discuss POW contribution to various sectors of the economy. To do this, I must do a process called georeferencing. I take a scanned map and line up points (such as cities, or tracing rivers and coastlines) from it with my base-map in the mapping software. Before I can do the process, though, I needed to get high quality scans of the Soviet maps.

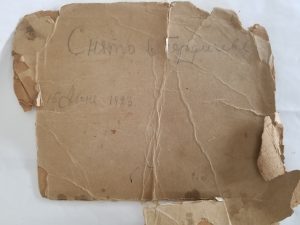

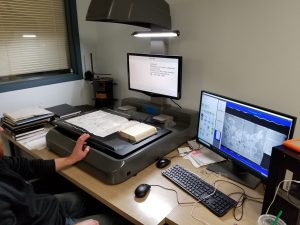

Based in the library, we have weekly drop-in hours for DH. People can come it and consult others in the room for help with their projects. In my case, I’m working with a GIS librarian, as well as a CLIR Fellow in Data Visualization who also has a GIS background. When discussing the georeferencing task with them, they introduced me to the library’s chief digitization specialist. She invited me on a trip to the library’s offsite storage location, where the digitization department is based for space concerns. The staff helped me scan a series of maps on special, face-up scanners at a very high quality. One issue with my map sources is that they are quite often large, fold out maps bound into thick books. These types of sources would be extremely difficult to scan on a traditional copy machine scanner like I have access to in my department. The library’s digitization scanners were face-up and had a special platform specifically for bound books that allowed the two sides of the spine to be at different levels to create a flat surface under the glass scanner face. The scanning specialist also saved the scans for me in the highest quality resolution, which is necessary to zoom in and do all the tracing and lining up of points more accurately.

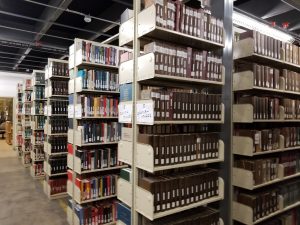

In addition to doing my scanning work, I was allowed to wander through the library’s offsite book storage. Not all university libraries keep all their books on the shelves of the library. As they acquire more books, older, rarely used books are taken to offsite storage areas. Many of my good book finds have been from seeing what was on the shelf near a different book that I found through a catalog search. This, unfortunately, is not possible with offsite books. However, the offsite librarians gave me free reign to wander around the offsite stacks. I searched in a few sections for the books that I use (generally Library of Congress DK books) to see if I had been missing any useful, older books.

Walking through the stacks, I felt like I was living out the archive scene from GoldenEye. I was super giddy to get to see the library technology and storage facilities, and the library staff was equally excited to show off their wares and help a lowly grad-student with her research. Make friends with the librarians. They will make your research life much less stressful, and you might get to take a fieldtrip to a cool school-based location.