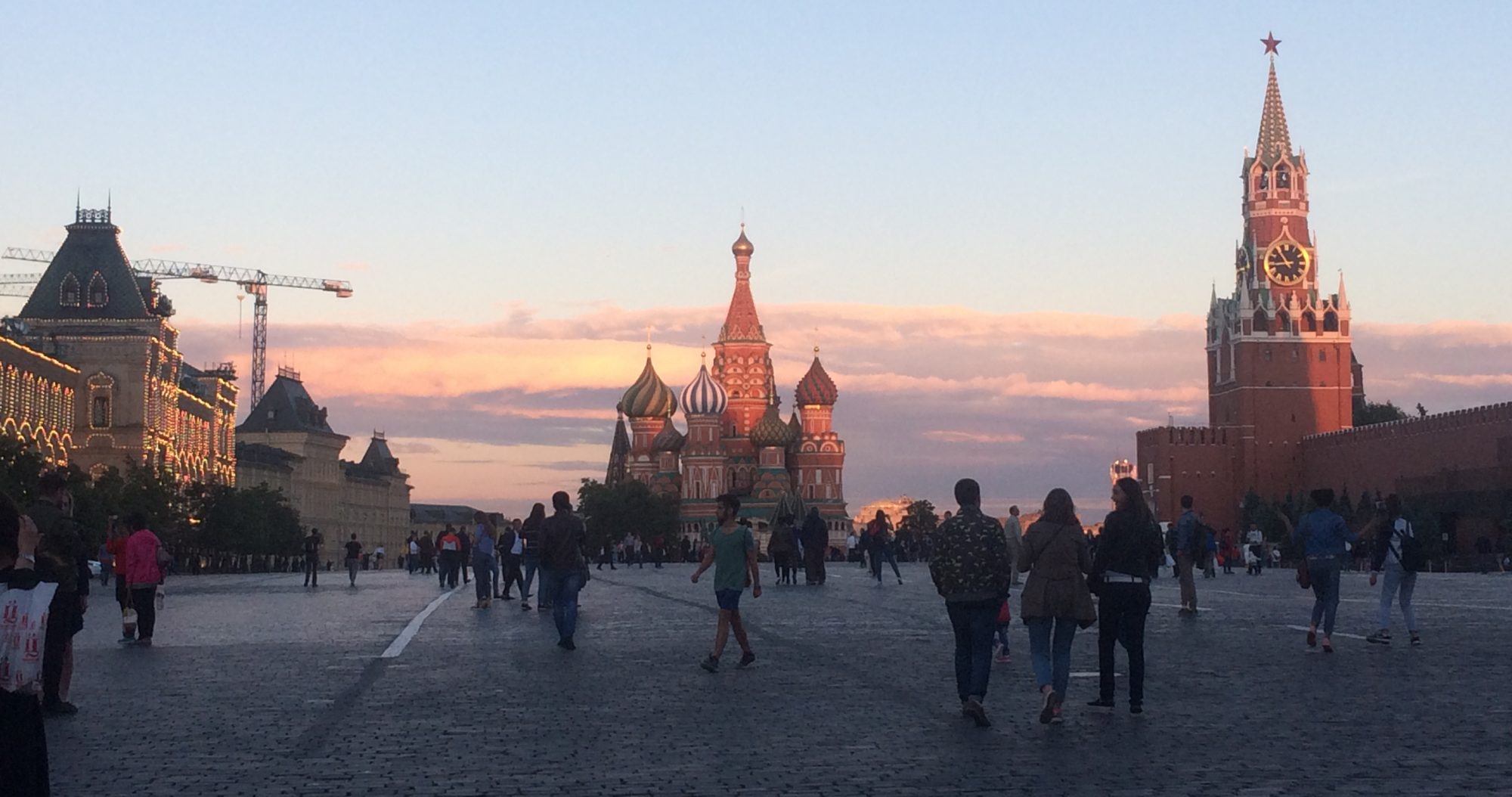

Today is my favorite Russian holiday, Victory Day. Every May 9th, Russians celebrate the end of the Second World War, or as they call it the Great Patriotic War. The day commemorates the surrender of Nazi Germany and the fighting in Europe. Commemoration of the war rose to its height in the USSR during 1960s and 1970s. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, celebration of the victory, while still an important date, was less of a state sponsored affair until the mid-2000s, when President Vladimir Putin brought the military parade back to Red Square. Ever since, it has been a massive national holiday complete with major celebrations around the nation.

Last year, I had the fortune to be in Moscow for the celebration. It was truly a spectacular day. This year, I woke up and watched the entire Moscow parade from my desk in Pittsburgh while drinking my morning coffee. The parade this year was quite interesting, and Putin’s annual address gives clues to the mindset of contemporary Russia. In this post, I will comment on some of the thoughts that popped into my head as I watched the parade.

The popular image of military parades on Red Square, complete with ICBMs, is a Soviet tradition. The main military parades, though, were held on November 7, the anniversary of the Russian Revolution. There were only a handful of Victory Day parades that were accompanied by military technology, generally those around major anniversaries. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the loss of November 7th as a holiday and parade worthy occasion, the display of Russian military might has transitioned to the anniversary of its most important victory.

This year, Putin opened the parade with an address that discussed both the importance of the memory of the Second World War as well as Russia’s stance on military strength and the global balance of power. He opened his speech by saying, “I congratulate you on Victory Day, a holiday that has always been, is, and will be the most dear and scared for every family in our large country.” Although public speeches are good forums for hyperbole, Putin said this statement in earnest. During the Second World War, the Soviet Union lost roughly 27 million citizens. No family was untouched by the damages and death of the conflict. It is indeed a sacred day for the memories of Russians.

Putin stated that it was the duty of Russians to keep remembering the war, and to never allow for the rewriting of history. He explicitly mentioned saving Europe and the world from the horrors of war, slavery, and the Holocaust. Mention of the Holocaust itself is already a radical break from the war memory of the Soviet Union, in which there was a policy of not “dividing the dead,” that is, not to highlight the suffering of any specific group during the war. A vast variety of Soviet citizens perished, and the Soviet state chose a policy of pan-Soviet remembrance versus individualism. Putin’s comments about the Holocaust and slavery, though, are a thinly veiled comment on the ongoing conflict with Ukraine. In the past few years, Ukrainian nationalists have celebrated some figures who fought for Ukrainian nationalism and independence amidst the Second World War. These persons are troubling, though, as they often collaborated with the Nazis in an attempt to realize these goals. Putin concluded his speech with a statement towards other nations. He commented on fragile global relations and stated that Russia is committed to “open dialogue on all matters of global security, ready for a constrictive equal partnership for the sake of agreement, and peace and progress on the planet.”

After Putin’s speech, the different groups of soldiers marched off of Red Square to make way for the technology. As usual, the motorized portion of the parade was led by a T-34 tank, the Red Army’s iconic vehicle of the Second World War.

This year, though, it was followed by ATVs bearing the names of the battle fronts of the war. Many staple tanks, troop carriers, and missile systems of the Russian army then progressed across Red Square. There was a well choreographed moment in which the band started to play the popular war song Katyusha while the modern missile launchers rolled past. Katyuhsa was the nickname for the Red Army’s mobile rocket launching trucks of the Second World War.

Taking from Soviet tradition, though, the annual show of military might included the public parade debut of a variety of military technology including varieties of armored fighting vehicles and supersonic jets. The focus of the new equipment this year was unmanned combat vehicles such as drones or remote-control armored devices for clearing minefields.

This year, the parade featured two guests of note. The most important of which was Benjamin Netanyahu, the Prime Minister of Israel. The parade commentary noted that this is the first year that Victory Day was celebrated as a national holiday in Israel. The parade covered also included a brief focus and shout out to a notorious, adoptive Russian citizen, Steven Segal.

Clearly, the Victory Day parade is not going to go anywhere under the leadership of Putin. The next few years of commemoration should prove to be interesting given Russia’s role in global politics. Next year’s parade should be fairly tame, though, in comparison to whatever will happen in 2020, the 75th anniversary of Victory Day.